Edmund Jones (1702–93) was a Calvinistic Congregationalist minister, born in Penllwyn in the parish of Aberystruth, Monmouthshire. This was a mountainous and forested landscape, popularly believed to be the abode of dark forces. He wrote two books dedicated to these agencies. The original was published in 1767, and a sequel, entitled A Relation of Apparitions of Spirits in the Principality of Wales, in 1780. They are collections of testimonies describing allegedly genuine encounters with spiritual entities, such as fairies, ghosts, devils, and witches. Jones’s works belong to a tradition of so-called spirit histories, written by Nonconformist ministers and Protestant and Roman Catholic clergymen, which marshalled accounts of the supernatural to vindicate revealed religion, prove post-mortem life, and administer an antidote against atheism and sadducism. He classified apparitions as those that were either visible or invisible, perceptual or auditory, and evil or good. The accounts were collected during his itinerancy around the parishes and counties of Wales, by word of mouth for the most part.

In 2003, I published an edition that incorporated the testimonies from Jones’ two books, as well as those referred to in his A Geographical, Historical, and Religious Account of the Parish of Aberystruth (1779). Jones’s accounts deal with how the lower orders of society in particular conceived the spiritual world. The narratives also preserve the peculiarities of the spirits’ noises, the hearers’ response to such, and the relationship of the sounds to the context. This was rural Wales prior to the industrial age, through which people habitually travelled by coach and on foot and horseback. He described its forests, woods, mountainsides, fields, lakes, rivers, coach-paths, and lanes as being inhabited with the noises of, variously, the hellish, heavenly, revenant, malevolent, fierce, and wild.

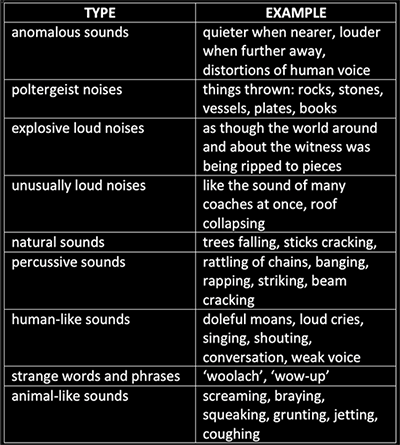

Witnesses heard sounds that echoed past events and prefigured future ones; sounds where there ought to be none; silence where there ought to be sound; sounds at odds with the nature of their cause; and sounds that travelled through the landscape in peculiar ways. The auditory apparitions were manifest in the forms of strange speech, spirits imitating the voices of the deceased, psalm-singing, angelic choirs, coaches and horses, woeful moans, the groans of the dying in extremis, quiet voices, animal-like sounds, tree-fall, strange whistling, and deafening sounds loud enough to disturb the fabric of the landscape in which they were heard. Many of the auditory attributes of spirit noises were adapted from the natural world and everyday experience. Their supernatural signification was summoned by the fearful concomitants of the phenomena, such as darkness (many of the auditions took place at night), the often strange and frightening visible aspect, and the unnerving modulations, exaggerations, and deformations of the auditory source. The acoustic emanation of spirits was sometimes more terrifying than their visual expression, rendering the hearer either seriously ill or incapacitated.

In 2003, I published an edition that incorporated the testimonies from Jones’ two books, as well as those referred to in his A Geographical, Historical, and Religious Account of the Parish of Aberystruth (1779). Jones’s accounts deal with how the lower orders of society in particular conceived the spiritual world. The narratives also preserve the peculiarities of the spirits’ noises, the hearers’ response to such, and the relationship of the sounds to the context. This was rural Wales prior to the industrial age, through which people habitually travelled by coach and on foot and horseback. He described its forests, woods, mountainsides, fields, lakes, rivers, coach-paths, and lanes as being inhabited with the noises of, variously, the hellish, heavenly, revenant, malevolent, fierce, and wild.

Witnesses heard sounds that echoed past events and prefigured future ones; sounds where there ought to be none; silence where there ought to be sound; sounds at odds with the nature of their cause; and sounds that travelled through the landscape in peculiar ways. The auditory apparitions were manifest in the forms of strange speech, spirits imitating the voices of the deceased, psalm-singing, angelic choirs, coaches and horses, woeful moans, the groans of the dying in extremis, quiet voices, animal-like sounds, tree-fall, strange whistling, and deafening sounds loud enough to disturb the fabric of the landscape in which they were heard. Many of the auditory attributes of spirit noises were adapted from the natural world and everyday experience. Their supernatural signification was summoned by the fearful concomitants of the phenomena, such as darkness (many of the auditions took place at night), the often strange and frightening visible aspect, and the unnerving modulations, exaggerations, and deformations of the auditory source. The acoustic emanation of spirits was sometimes more terrifying than their visual expression, rendering the hearer either seriously ill or incapacitated.

Little scholarly attention has been given to historical examples of auditory apparitions. In part, this is because spirit sounds, like all other types of auditory phenomena at this time, were intangible and impermanent; they left no scrutable residue. In contrast, visual manifestations of spirits, while equally evanescent, could be represented and made tokenly permanent in engravings and drawings based upon the witnesses’ testimony. Their envisionings (when not encountering spirits that looked like living human beings or animals (until they disappeared)) deployed simple but nonetheless effective collagings and hybridisations, distortions of shape, proportion, and size, anomalous movements, incomplete renderings of everyday people, things, natural elements, and abstract forms – such as a pyramid, sphere, and bowl.

Prior to the invention of sound recording and playback technology, spirit sounds could neither be captured, other than as a memory or textual account, nor recalled other than through verbal or written testimony (which functions Jones’s collection fulfils.) As in the case of the visual accounts of spirits, witnesses described auditory manifestations in terms of attributes associated with known and natural acoustic phenomena. Similarly, these attributes are variously combined, amplified, disrupted, recontextualized, and re-interpreted in such a way as to evoke a sense of the unworldly and threatening. For example, there are several instances in which the customary experience and operation of sound was inverted. The noise that several spirits made was loud afar-off but grew progressively quieter as the spirit approached. Poltergeists produced noises, in the manner of the living, by either throwing or beating things against other things. Disembodied or invisible spirits frequently imitated humans and animal noises, so as to appear either entirely natural, or in some manner distorted, or either far louder or softer than their customary volume. For instance, the voice of one female spirit was said to be ‘as if it were a drum’. There are accounts, too, of angels singing, as well as fairies playing music. Other sounds were like those associated with nature and material culture, such as trees falling, sticks cracking, a roof collapsing, and iron chains rattling.

In some accounts, what the witness perceived was so peculiar that it could only be described in terms of an approximation to something in the ordinary world. One witness, on travelling at night across Illtyd Mountain, Breconshire, ‘all of a sudden … heard on his right hand a sound as strong and loud as five or six coaches could make at once.’ In another account, it is said, a woman heard a spirit mastiff scream ‘so loud and strong that the earth moved under her’. In Wales, as elsewhere before the Industrial Revolution, the loudest noises anyone heard were thunderclap, a gun-powder explosion, gunshot, an ironmonger’s hammer upon the anvil, and coach wheels on cobblestone. So, whatever the witnesses thought they had heard was far in excess of customary volume levels.

Noisome Spirits returns some of these narratives to a sonic experience. In so doing, it seeks to make the witnesses’ audition sensible, by presencing the sounds and – following Jones’ own determination – providing a ‘vivid account’ of apparitions … albeit acoustically. The objective, however, is not to present a simulacrum of the original sounds but, rather, to summon their sonic essence and the witnesses’ sense of the dread and otherness associated with them, imaginatively and abstractly.

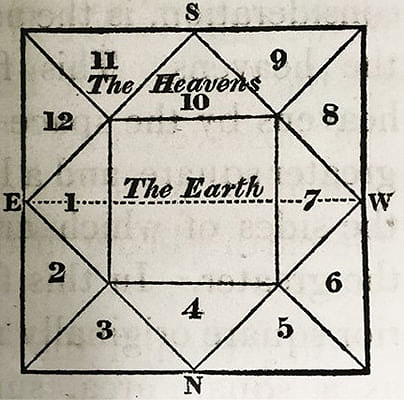

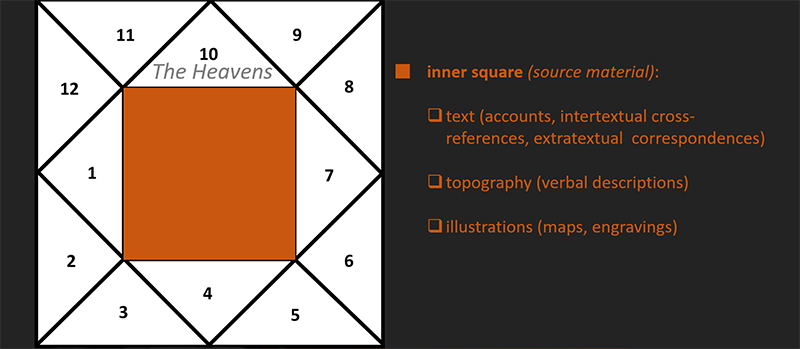

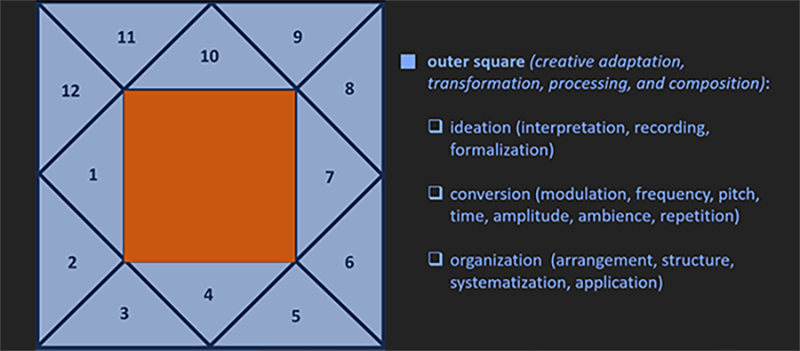

The processes and considerations brought to bear upon these account in adapting them to sound works are tutored by a cosmological framework was at the heart Jones’s outlook on life. He drew astrological charts to determine the course of his ministry and itinerancy. The notion that the stars indicated (rather than determined) the course of his life was congruent with his Christian beliefs. The celestial sphere was, after all, God's handiwork, and he had guided the Magi to the Christ-child by means of a star (Matthew 2.1-11). The central square represents the Earth and the outer square, the heavens. The latter is divided into twelve compartments (or houses) to represent the lunar months. Within this structure, Jones charted the position of the constellations, planets, and their procession. I have adapted this schema as a way of representing to myself two domains and their interactions: first, the source material (denoted by the inner square); and secondly, the conceptualization, adaptation, and processing of such (denoted by the outer square).

As in the case of the previous releases in The Aural Bible series, the source material determines the process of composition. (That is to say, the creative outcome is governed by the object under scrutiny.) Jones’s accounts and the original medium of their dissemination – the printed book – serve as both the ‘score’ for, and ‘instrument’ of, their translation into a sonic form. The sounds are derived from, for example: the text of the accounts read aloud; the pages of a book being turned and riffled though; crumpling paper; and the noise made by a letterpress machine (like that which would have been used to print Jones’s books).

Moreover, the sounds of acoustic apparitions were often described in terms of what was known and comprehensible. For example, a witness claimed that the noise one spirit made was equivalent to the volume that five or six coaches made. Another described a female spirit’s voice as sounding like a drum. The Noisome Spirits suite reverses the polarity of this principle. Thus, familiar and very earthbound objects and actions are transformed into the likenesses of the screams, snarls, voices, and ferociously destructive outbursts of the dead, damned, and demonic.

The semantic content of Jones's accounts, and the order of the events described in the narratives, inform the compositions’ substance, conception, structure, and development. A variety of natural, supernatural, and man-made sounds are referred to in the texts. They are either imitated or evoked using the derived sounds. The 'Source Text' (as it is referred to in the individual track descriptors) serves both as a 'libretto' and fountainhead of the compositional material. These texts have been variously slowed down or speeded up, played forward or in reverse, edited, reordered, modulated, and superimposed.

Some of the natural sounds mentioned in the accounts are also re-presented by repurposing (using the same strategies), recordings made of the natural world. Thus, for example, the sound of breaking twigs, heard in 'Such a noise as if all the hedges about were tore to pieces', is transformed into that of hedges disintegrating. Nothing is what it appears to be. The only exception is heard at the conclusion of ‘John ab John’: the sound of a solitary blackbird singing (albeit multiplied many times and rendered at different speeds), which I recorded in my garden on April 24, 2020, during the initial Covid-19 lockdown.

Noisome Spirits is the fourth release in The Aural Bible series. The series deals with the Judaeo-Christian scriptures as the written, spoken, and heard word. It explores the cultural articulations and adaptations of the Bible within the Protestant tradition. The works on the album embark upon a critical, responsive, and interpretive intervention with aspects of its sound culture. The websites that accompany the series’ CD albums are dynamic. Material will be added, and sub-sections fleshed-out, as opportunities for the work to be presented, discussed, reviewed, and broadcast, present themselves.

John Harvey

March 2021

Throughout the site, text in white indicates a hyperlink.

Moreover, the sounds of acoustic apparitions were often described in terms of what was known and comprehensible. For example, a witness claimed that the noise one spirit made was equivalent to the volume that five or six coaches made. Another described a female spirit’s voice as sounding like a drum. The Noisome Spirits suite reverses the polarity of this principle. Thus, familiar and very earthbound objects and actions are transformed into the likenesses of the screams, snarls, voices, and ferociously destructive outbursts of the dead, damned, and demonic.

The semantic content of Jones's accounts, and the order of the events described in the narratives, inform the compositions’ substance, conception, structure, and development. A variety of natural, supernatural, and man-made sounds are referred to in the texts. They are either imitated or evoked using the derived sounds. The 'Source Text' (as it is referred to in the individual track descriptors) serves both as a 'libretto' and fountainhead of the compositional material. These texts have been variously slowed down or speeded up, played forward or in reverse, edited, reordered, modulated, and superimposed.

Some of the natural sounds mentioned in the accounts are also re-presented by repurposing (using the same strategies), recordings made of the natural world. Thus, for example, the sound of breaking twigs, heard in 'Such a noise as if all the hedges about were tore to pieces', is transformed into that of hedges disintegrating. Nothing is what it appears to be. The only exception is heard at the conclusion of ‘John ab John’: the sound of a solitary blackbird singing (albeit multiplied many times and rendered at different speeds), which I recorded in my garden on April 24, 2020, during the initial Covid-19 lockdown.

Noisome Spirits is the fourth release in The Aural Bible series. The series deals with the Judaeo-Christian scriptures as the written, spoken, and heard word. It explores the cultural articulations and adaptations of the Bible within the Protestant tradition. The works on the album embark upon a critical, responsive, and interpretive intervention with aspects of its sound culture. The websites that accompany the series’ CD albums are dynamic. Material will be added, and sub-sections fleshed-out, as opportunities for the work to be presented, discussed, reviewed, and broadcast, present themselves.

John Harvey

March 2021

Throughout the site, text in white indicates a hyperlink.